Introduction: What is Pongal?

Pongal is one of the most important traditional festivals of South India and a cornerstone of Tamil cultural identity. Celebrated primarily in Tamil Nadu and by Tamil communities across the world, the pongal festival is a harvest thanksgiving that expresses gratitude to nature for agricultural abundance. At its heart, Pongal is a celebration of food, farming, family, and faith, marking the successful completion of the agricultural cycle.

When people search about Pongal or look for about pongal festival in English, it is commonly described as a four-day harvest festival that honors the Sun God, cattle, and the land that sustains human life. Unlike many religious festivals tied to mythology alone, Pongal is deeply rooted in everyday agrarian reality. It celebrates the tangible rewards of labor—new rice, milk, and sugarcane—and acknowledges the interconnectedness between humans, animals, and natural forces.

Etymology: meaning of the word Pongal (“to boil over” / abundance)

The word Pongal originates from the Tamil verb pongu, meaning “to boil,” “to rise,” or “to overflow.” This meaning is not symbolic alone but enacted literally during the festival when milk and freshly harvested rice are boiled together until they spill over the cooking vessel. This overflowing is considered highly auspicious and is welcomed with joyful exclamations.

The act of boiling over represents abundance, prosperity, and the hope that happiness and wealth will overflow into one’s home throughout the coming year. Linguistically and ritually, the name Pongal perfectly captures the essence of the festival—plenty shared openly and gratefully.

When it’s celebrated: Tamil month of Thai (mid-January) and relation to Makar Sankranti / Uttarayana

Pongal is celebrated in the Tamil month of Thai, which typically falls between January 14 and January 17 in the Gregorian calendar. This period marks the Sun’s transition into Capricorn (Makara), initiating its northward journey known as Uttarayana. Across India, this solar movement is celebrated as Makar Sankranti under different regional names.

Thai Pongal, the second day and main observance, is dedicated to the Sun God (Surya) in recognition of his role in agriculture. The longer daylight hours following Uttarayana symbolize growth, renewal, and life-giving energy—making this period ideal for a harvest festival.

Quick snapshot: four-day harvest festival in Tamil culture

In summary, Pongal is a four-day harvest festival that celebrates nature, food, and community.

• Bhogi marks renewal and letting go of the old

• Thai Pongal centers on gratitude to the Sun

• Mattu Pongal honors cattle

• Kaanum Pongal strengthens social bonds

Together, these days form a complete cycle of thanksgiving and renewal in Tamil culture.

Historical Origins and Evolution

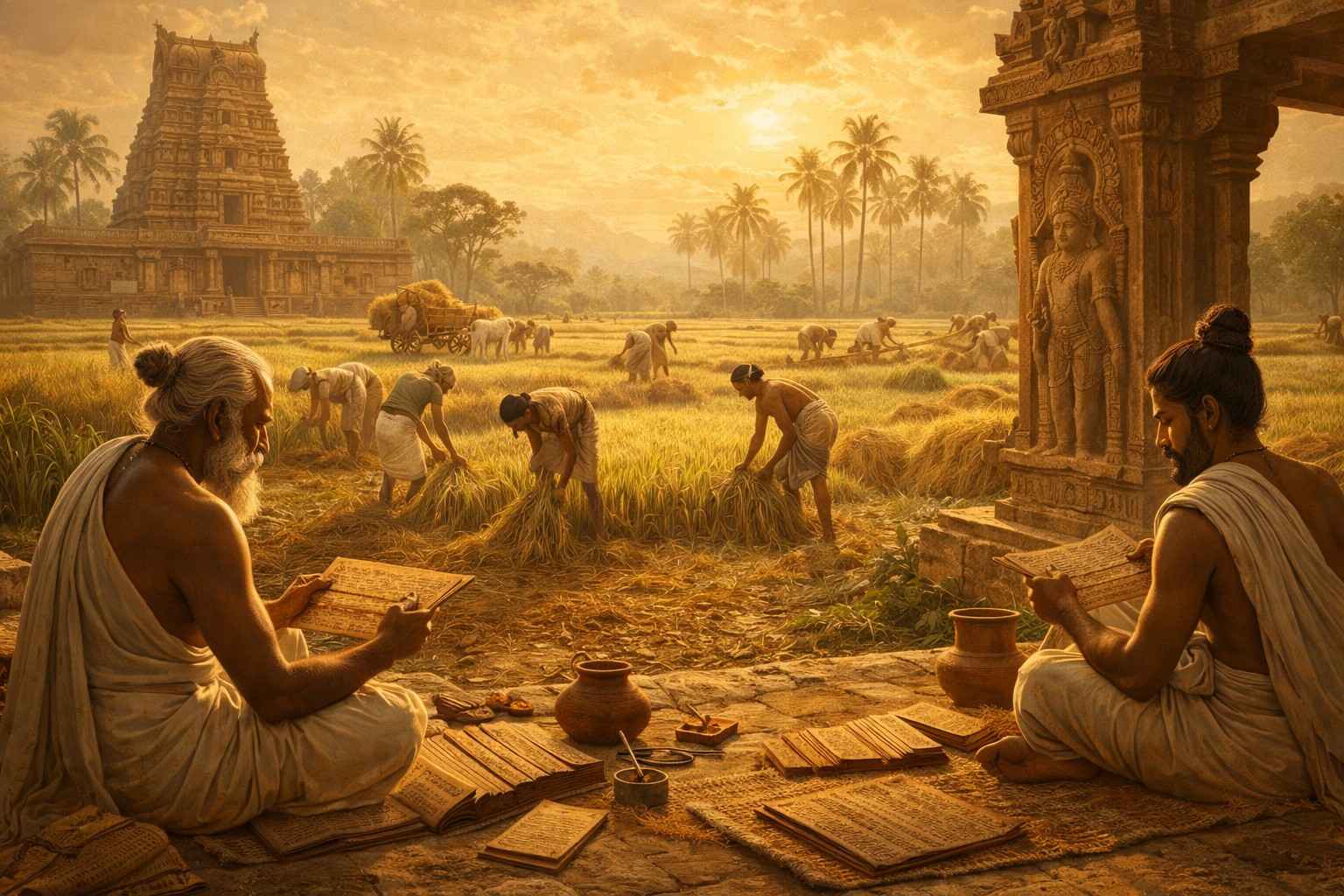

Ancient / literary references: Sangam literature and medieval temple inscriptions

The origins of Pongal can be traced back more than two thousand years. Sangam literature, dating roughly between 300 BCE and 300 CE, provides evidence of agrarian life deeply tied to seasonal cycles. Poems describe rice cultivation, cattle rearing, rain dependency, and communal feasting—elements that align closely with modern Pongal practices.

While the term “Pongal” may not always appear explicitly, the themes of harvest gratitude and ritual cooking are clearly present. These early texts suggest that the festival evolved organically from everyday farming practices rather than being imposed by religious doctrine.

Temple and royal records: Chola/Vijayanagara era mentions of Pongal rituals

During the medieval period, temple inscriptions from the Chola and later Vijayanagara dynasties provide concrete documentation of Pongal rituals. These inscriptions record donations of rice, milk, ghee, and jaggery to temples during the harvest season. Some specify large-scale communal cooking and food distribution, indicating that Pongal had become an organized public festival.

Royal patronage helped formalize Pongal observances, integrating household rituals with temple ceremonies. The association between temples, agriculture, and royal authority strengthened Pongal’s cultural significance.

How the festival changed over centuries

Over time, Pongal transitioned from a temple-centered and court-supported ritual into a predominantly household and community celebration. As agrarian society decentralized and urbanization increased, the festival adapted while retaining its symbolic core.

Clay pots replaced temple cauldrons, courtyards replaced temple grounds, and families became the primary units of celebration. Despite these changes, the essential elements—harvest rice, gratitude, and sharing—remained intact, showing Pongal’s remarkable continuity.

The Four Days — Rituals & Meaning (Bhogi, Thai Pongal, Mattu Pongal, Kaanum Pongal)

Bhogi (day 1): cleaning, bonfire of old items, new-beginnings symbolism

Bhogi marks the beginning of the Pongal festival and focuses on renewal. Homes are thoroughly cleaned, and unused or broken items are discarded. Traditionally, these old items are burned in a bonfire early in the morning, symbolizing the destruction of negativity and stagnation.

The ritual emphasizes psychological and material cleansing, preparing households to welcome prosperity. Bhogi reflects a universal human need to let go before moving forward.

Thai Pongal (day 2 — main day): cooking the pongal dish

Thai Pongal is the most important day of the festival. Early in the morning, families prepare the pongal dish by boiling new rice and milk until it overflows. The pot—often a clay vessel—is placed outdoors to receive sunlight, reinforcing the connection with the Sun God.

Prayers are offered to Surya, thanking him for sustaining crops and life. This moment defines the essence of pongal celebration—gratitude expressed through food, prayer, and shared joy.

Mattu Pongal (day 3): honoring cattle

Mattu Pongal acknowledges the role of cattle in agriculture. Cows and bulls are bathed, decorated with garlands, bells, and sometimes painted horns. They are fed special food, including pongal, fruits, and sugarcane.

In rural areas, cattle processions and traditional games celebrate the human–animal partnership essential to farming life.

Kaanum / Kaanum Pongal (day 4): social visits, community outings

The final day, Kaanum Pongal, is dedicated to social bonding. Families visit relatives, exchange gifts, and enjoy outings. Young people seek blessings from elders, reinforcing intergenerational ties.

This day balances ritual seriousness with leisure and joy, completing the festival cycle.

Culinary Traditions and Symbolic Foods

Pongal (the dish): varieties and ingredients

The festival’s name comes from its signature dish. Sakkarai Pongal, the sweet version, is made from new rice, milk, jaggery, ghee, cardamom, and nuts. Ven Pongal, a savory dish of rice and lentils seasoned with pepper and cumin, is equally popular.

In contemporary households, cooker Pongal is widely prepared using pressure cookers. While the method has modernized, the ritual intention remains unchanged.

Other festive foods

Sugarcane is inseparable from Pongal celebrations, symbolizing sweetness and agricultural success. Vadai, payasam, fruits, and regional snacks complement the pongal special meal, adding diversity and richness.

Kitchen ritual & offering

Cooking Pongal is a sacred act. Clay pots are often decorated through pongal paanai painting, especially in homes and schools. The first portion of food is offered to deities before being shared, reinforcing the idea of communal abundance.

Social, Cultural and Agricultural Significance

Agrarian context

Pongal is fundamentally an agricultural festival. It thanks the Sun, rain, soil, farmers, and animals that make food production possible. This holistic worldview emphasizes balance with nature rather than dominance over it.

Community life and cultural expression

Kolam designs, folk songs, dances, and rural sports strengthen social cohesion. These practices reinforce shared values and collective identity, forming the broader pongal theme of unity and gratitude.

Diaspora & cross-border celebrations

Tamil communities worldwide celebrate Pongal in temples, community halls, and homes. Even far from farmlands, the festival preserves cultural memory and identity.

Modern Practices, Tourism, and Contemporary Issues

Urban vs rural celebrations

Urban celebrations adapt Pongal to modern living—using pressure cookers, shared spaces, and time-efficient rituals—while rural areas often maintain traditional outdoor practices.

Pongal as cultural tourism

Tourism initiatives promote Pongal as a living heritage festival. Demonstrations of kolam, food preparation, and pongal paanai painting attract visitors seeking authentic cultural experiences.

Contemporary debates & sustainability

Modern Pongal discussions include animal welfare, environmental sustainability, and eco-friendly practices. Many communities now emphasize organic farming, waste reduction, and green celebrations.

Conclusion

Pongal is more than a festival—it is a philosophy of gratitude. By honoring the Sun, farmers, cattle, and community, it reinforces humanity’s dependence on nature. Rooted in ancient agrarian traditions yet flexible enough to adapt to modern life, Pongal continues to thrive across villages, cities, and global diasporas.

Its simple act of sharing the season’s first harvest remains a powerful reminder that abundance is meaningful only when shared, and prosperity is sustainable only when grounded in respect for nature and community.

If you want to learn more about Indian festivals, you can explore here.dionfest